Sunday, July 18, 2021

Billy No Mates

Tuesday, July 13, 2021

A Smelly Subject

Friday, July 9, 2021

Yellow Or Grey

It’s a subject that cropped up at Another Bird Blog when a reader suggested via a comment that my image of a Yellow Wagtail was in fact a Grey Wagtail. The photograph is the one below.

And for anyone looking for a top quality field guide to the birds of Great Britain and Ireland I recommend the following three books:

That's all for now. Back soon with Another Bird Blog. I hope to fix the half a header problem soon, perhaps via Blogger or through a helpful and HTML knowledgeable reader.

Sunday, July 4, 2021

Ones And Twos

Thursday, July 1, 2021

Martin More

Tuesday, June 29, 2021

Spotted Again

We have a further sighting of a Spotted Flycatcher we ringed at Oakenclough back on 7 September 2019.

Thanks to the person who found Spotted Flycatcher AKE3299 as a breeding bird in May and June 2021 we have an unexpected and extraordinary record. I will quote from the BTO notification to us. Bold text is mine.

Species: Spotted Flycatcher

Ring Number: AKE3299

Finding date: 27 June 2021

Place: Washburn Valley, North Yorkshire

Sight Record by Non Ringer- Metal Ring Read In Field

Remarks: 4 chicks. Video footage available.

Spotted Flycatchers from LeedsBirder on Vimeo.

I contacted Leeds Birder, Paul Wheatley and asked permission to use his super detailed video as above. Paul clearly worked extremely hard, perhaps frame by frame of the footage to read the combination of letters and numbers on the ring so as to try and discover the origins of AKE3299. A fine piece of detective work!

I was able to point Paul to the Another Bird Blog post of 7 September 2019 and advise that AKE3299 was one of two Spotted Flycatchers caught that day, both juvenile birds of the year.

https://anotherbirdblog.blogspot.com/2019/09/spotted-saturday.html

The two flycatchers of that day were caught hours apart but may have arrived together that morning of 7 September during the window of fine weather that followed a week and more of September winds.

Almost certainly AKE3299 was born in Yorkshire in the summer of 2019 and returned there to breed in the same area in 2020 and in 2021. Its autumnal migrations in both years would take it across the Pennines on a south westerly path through England, France and Spain and then towards Africa where it would spend the winter. Spotted Flycatchers are late to return to the UK and it can be late May before they are seen back on territory.

Spotted Flycatchers cross the Sahara Desert twice a year on

their way to and from wintering areas in sub-Saharan Africa, where a loss of

woodland may have reduced survival. Another explanation is that breeding

success has fallen because of fewer insects, loss of habitat and because of

increased predation by woodland predators such as grey squirrels.

Spotted Flycatchers have declined substantially in recent

years and are designated as a Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP) species. They are

popular birds as they frequently nest close to house walls or in hanging

baskets. They fly from prominent perches to catch insects, and are an attractive

sight in country villages. Their numbers

have declined by about 80% over the past three decades.

Thanks again to Leeds Birder for this brilliant record of a Spotted Flycatcher and for proving the value of reading ring numbers in the field. Paul and team have more videos on Vimeo that make for excellent viewing.

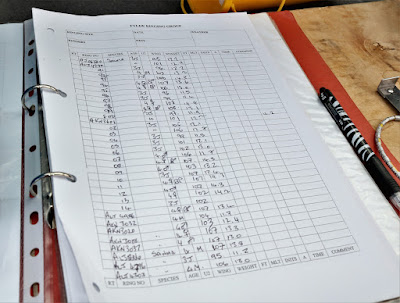

News next time of our catch of Sand Martins on Tuesday morning.