I promise not to mention the weather again except to say that it has not improved and doesn't look any better for the next week either.

In the absence of recent local news or birding from me, I devote today to a rehash of a book review. this is from December 2012 with a book I described at the time as "a most unusual, probably unique book about birds" - The Unfeathered Bird.

When my friends at Princeton University Press promised to forward a copy of the book, and from the modest title, not quite knowing what to expect, I Googled “The Unfeathered Bird” for an initial flavour of the contents:

“A unique book that bridges art, science, and history

- Over 385 beautiful drawings, artistically arranged in a sumptuous large-format book

- Accessible, jargon-free text - the only book on bird anatomy aimed at the general reader

- Drawings and text all based on actual bird specimens Includes most anatomically distinct bird groups Many species never illustrated before”

A succinct but descriptive summary and one which gives a clearer idea of the book’s innards while leaving room for discovery. It would be a book unlikely to fit into the category of a “Bird Book” as owned by probably the majority who go out in the field in search of birds; bird watchers or birders who as a matter of course do not normally invest in books which are overly scientific, too arty, or lacking in the immediacy of news and information their pursuit demands.

Maybe then it would appeal to a lesser number of birders with a scientific and/or artistic bent, ornithologists or bird artists alone, bird photographers, biologists, natural historians, and/or artists who use a variety of mediums?

From Google I found information about the book’s author Katrina van Grouw. In 1992 she gained an MA in Natural History Illustration for her illustrated thesis on bird anatomy for artists. It was by following and researching this topic further that Katrina's aim to write The Unfeathered Bird became a burning desire, an ambition finally realised in the publication of the book in 2012.

From other perspectives Katrina’s ornithological knowledge, including skills in preparing bird specimens and in taxidermy won her a curator’s position in the bird skin collections at London’s Natural History Museum, where she remained in the post for seven years before leaving in 2010 to concentrate on completing The Unfeathered Bird.

Katrina is also a qualified bird ringer, having travelled widely on international bird ringing expeditions in Africa and South America. We met briefly during a BTO ringer's conference a number of years ago, towards the end of a typically long and enthusiastic evening of ringers sampling the local brew while putting both the world and the BTO to rights. I don't recall much of the discussions but I am fairly certain I spent the next day of the conference with a banging head ache.

Back to the job in hand and what of the book itself? It consists of the customary introductory pages, followed by two other sections. Part One is a generic section based upon the basic bird structure of trunk, head and neck, hind limbs, and wings & tail. Part Two is entitled Specific and deals with the bird groups of Acciptres, Picae, Anseres, Grallae, Gallinae and Passeres, each with subdivisions containing the more familiar names e.g. owls, herons, swifts etc. If by modern day standards the order of appearance appears unorthodox it is because the author ordered the chapters in a system concerned only with outward structural appearances, and to “avoid the swampy territory of taxonomic debate” the first truly scientific classification of the natural world, the Systema Naturae of Linnaeus.

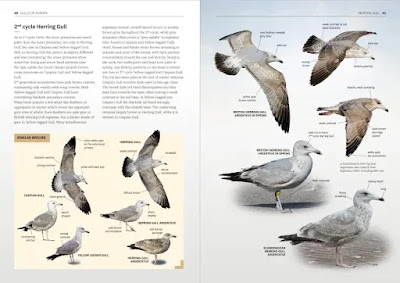

The Unfeathered Bird covers more than 200 species of the world in more than 385 illustrations, many of the detailed drawings simply superb, others just truly amazing. Many of the sketches depict what goes on just under or on the surface of a bird without its feathers, often birds in typical postures or engaged in bird-like behaviour such as the act of flying itself, diving underwater, feeding, or displaying etc. Each plate has a corresponding page or more of text which describes the relationship between that particular bird or bird family’s anatomy to their evolution and the daily lifestyle and behaviour. Other less animated plates show particular features such as skulls, bills, feet or whole skeletons; in places this can be a whole double spread page - for instance the skulls and bills of Darwin’s finches, or the exquisite and perhaps life-size illustration which depicts the skull and bill of both Marabou and White Stork.

Notwithstanding the book’s both highly artistic and technical approach it’s good to see Katrina dropping a splash of humour into many drawings; witness the skeletal Robin on the spade handle, or the skeleton of a Wilson’s Petrel splashing daintily through the waves. And Katrina, only a bird ringer forever scarred by the feet of a Coot could have depicted those huge, cruel instruments with such love, detail and accuracy.

As one whose attempts at drawing birds is simply laughable I can only marvel at the skill, precision and sheer artistry involved in such an obvious labour of love displayed in almost 400 drawings. Katrina seems especially good at drawing feet, a part of the bird’s anatomy which many budding bird artists avoid by depicting their subject in vegetation or water. Here’s their chance - study The Unfeathered Bird and see how it’s done.

I’d be doing an injustice to Katrina were I to reproduce her drawings from my own photographs, especially when many are available online via Katrina’s own website, the publishers or the likes of Amazon.

I’d be doing an injustice to Katrina were I to reproduce her drawings from my own photographs, especially when many are available online via Katrina’s own website, the publishers or the likes of Amazon.

As a taster below are a couple of my simple favourites - the foot, toe and claws of a Grey Heron and then the head and neck of the same species.

Grey Heron - Princeton Press

Grey Heron - Princeton Press

I should mention that the majority of the drawings are reproduced in sepia tones, muted colours which work extremely well when set against the off-white background of the superior quality paper used. In fact the whole volume is beautifully produced with a look, feel and aroma of excellence.

The many plates will be the first port on an initial introduction to the book, a natural enough occurrence but one that should not detract from the text of descriptions, explanations and discussions which accompany the illustrations. Each and every section of the text material contains highly readable facts about our feathered friends.

That’s pretty much a précis of The Unfeathered Bird - art, history, geography, biology, evolution and birds, all rolled into one. And as the author is at pains to point out in the Introduction - “This book is not an anatomy of birds. That is to say, you won’t find any difficult Latin words or scientific jargon. You won’t learn much about the deep plantar tendons of the foot or the comparative morphology of the inner ear. Nothing beneath the skeleton is included—no organs or tissues; no guts or gizzards. There’s no biochemistry and very little physiology. This is really a book about the outside of birds. About how their appearance, posture, and behaviour influence, and are influenced by, their internal structure.”

Bird Skulls - Princeton Press

To go back to my original question then. Yes, here is a book with a wide appeal, a book which deserves to be studied by birders with a scientific and/or artistic bent, ornithologists, bird artists, bird photographers, biologists, natural historians, and artists of all persuasions. The author states that the original intention was a book aimed at artists and it was only during the early stages that she realised it could have wider appeal. In my opinion it was a realisation which has come to fruition in a beautifully crafted, scholarly and ultimately fine book.

The Unfeathered Bird is still available from Princeton Press.

An update. In 2021 Katrina gained a scholarship to study bird

evolution as a PhD at Cambridge University. As far as I know she is

well on with writing Volume Two of the Unfeathered Bird. And given her immense skills as artist and author she is probably busy with lots of other projects.

Take a look at my review of Katrina's second book published in 2020 - Unnatural Selection.

Katrina's drawing of geese from Unnatural Selection hangs in our hallway where visitors see it upon arrival and where I pass each day to my "office".

Geese - Katrina van Grouw

This week Another Bird Blog is linking to I'd Rather Be Birdin and Eileen's Saturday. Be be sure to check them out.