Yet again there's no birding due to never ending bad weather. Everyone is heartily sick of the now 4 months of incessant rain, perpetual wind and everlasting grey skies in days that are no good for bird, man nor beast.

Today and to keep the blog up and running, I am posting a reprise of a book review of 2022, a book based upon real science, one I labelled my "Bird Book of 2022". Here it is below with a few alterations and additions to bring the review bang up to date.

How Birds Evolve is a book released in the US in October 2021 and now at large in the UK from 4 January 2022. I suspect it’s late for publication caused by disruptions to business operations and normal life of recent months. Only recently did Princeton send a copy for review via Another Bird Blog and I do not understand why it only now appears in the UK, some 4 months later than the North American release.

Let me say right from the outset that How Birds Evolve is an outstanding book, one that had I seen a week or two before would have elicited a “buy” recommendation as a Christmas gift 2022 for the birder in your life. Read on to discover why this is a book every birder should read and own.

“How Birds Evolve - What Science Reveals About Their Origin, Lives, and Diversity” is the title of the 320 page volume by Douglas Futuyma. The author is Distinguished Professor Emeritus in the Department of Ecology and Evolution at Stony Brook University, State University of New York. His books include Evolution and Science on Trial: The Case for Evolution. He is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the National Academy of Sciences. These are immaculate credentials from someone who describes himself as an “enthusiastic birder” and whose observations, experiences and ornithological studies in over 50 countries can be found throughout the book.

A simple explanation to the science of birds’ origins is that birds grew from a group of meat-eating dinosaurs called theropods about 150 million years. Here were animals that survived in many different habitats, beings that evolved into the present day 11,000 bird species across the world. With such a close relationship to the extinct dinosaurs, how and why did birds survive? The answer is a combination of things: their small size, the fact they can eat a lot of different foods and have an ability to fly. These ancient birds looked quite a lot like small, feathered dinosaurs and they had much in common - their mouths still contained sharp teeth that over time evolved into beaks. After more than 140 million years in charge, the dinosaurs' reign came to an abrupt end when a huge asteroid strike and massive volcanic eruptions caused disastrous changes to the environment. Most dinosaurs went extinct while birds with winged feathers and the ability to fly remained until today, more than a little changed, but birds now near an extinction of their own.

Each of the chapters of How Birds Evolve has a sub title that more fully suggests to the reader the overall flavour, focus and the detailed content within. This sub-titling is useful to someone like me who on first acquaintance with a book likes to browse the parts, maybe even begin to read a book in the “wrong” order so as to match with a special interest while beginning to familiarise with an author’s style.

With twelve Chapters and over 300 pages, How Birds Evolve has so many highlights, so many fascinating, illuminating and enlightening segments that it’s almost impossible and perhaps unfair to pick my own particular favourite when other readers would choose differently. But, here goes.

The first chapters, 1) In the Light of Evolution: Birds and 2) Evolutionary Science and Parrots, Falcons, and Songbirds: The Bird Tree of Life are unavoidably technical in their use of scientific descriptions and terminology for which the author both explains and apologises in advance. There sections include partly challenging diagrams, illustrations or charts where prior experience, knowledge and/or reading are desirable but certainly not mandatory e.g. terms like DNA, Messenger RNA, phylogeny, genomes.

A determined and persevering read of the text while studying the diagrams/charts will ultimately reward the reader by enabling a thorough enjoyment and understanding of later chapters and the whole book. Every one of the 12 Chapters is jam-packed with insightful narrative into the lives of birds together with accounts of how, where, when and why the rich diversity of birds is an important aspect of evolutionary biology.

The three chapters ‘Highlights of Bird History’, ‘Finches and Blackcaps’ and ‘The Ruff and The Cuckoo’ I found especially entertaining and instructive because a number of the pages focused on familiar and recent topics.

The author described how in real time of 2017 Galapagos scientists observed the development of a new lineage of Darwin's finches, and showed how under the right conditions, evolution can occur over as little as two generations.

Futuyma relates how ornithologists at the University of Freiburg studying Blackcaps in two areas of Germany, 500 miles apart found that birds which spent winter in Spain had more in common genetically with their Spanish sun-loving counterparts than they did with their UK-wintering neighbours who bred in the same area. This led to the real possibility that the Spanish and UK-wintering groups of Blackcaps could be on their way to becoming two different species.

The author introduced me to the theory of ‘cultural evolution’, a change us oldies witnessed in the UK during the years of foil topped milk bottles standing on our wintery doorsteps and when Blue Tits were forced to change their daily behaviour by pecking holes through the foil to reach the sustenance below. We also discover that passerines learn many aspects of their songs from parents or neighbours whereby regional populations often diverge to form local dialects, something I have observed in the case of Yellowhammer, Chaffinch and Linnet.

Remaining chapters continue in the same vein, pages crammed with good reading and packed with knowledge about the causes of variation within bird populations and several species that each tells a special, unexpected and therefore fascinating story. UK readers will enjoy the sections that feature Ruff, Collared & Pied Flycatcher and Snow Goose. There’s absorbing discussion about polymorphism in respect of a number of types of birds such as skuas, hawks and owls; for instance, 69 of the world’s 206 owls are classified as polymorphic for colour, usually grey or rufous, differences that arose out of the variation of evolution.

The ancient Hoatzins of South America are avian cows. They eat leaves. They harbour bacteria in their crop that break down plant cellulose into sugars that the bird can use, just as cows and other ruminants do - convergent evolution at the biochemical level. Hoatzins climb trees with the help of claws on the point of their wings, a stage in the evolution of feathers. I decided that Chapter 6 How Adaptations Evolve which contains chart illustrations of bills, feathers, and ‘adaptations for climbing trees’ is a masterpiece of its own in what became a simply brilliant, entertaining and instructive chapter.

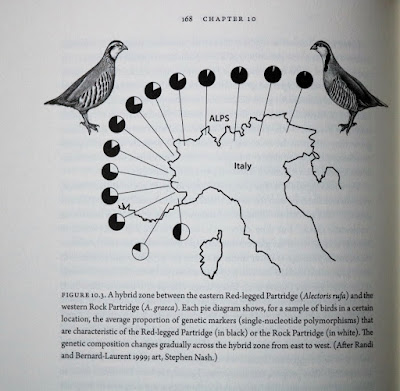

But there’s more, from tales and experiences and journeys around the globe where the author takes us from east to west to learn the genetic differences of Rock Partridge and Red-legged Partridge, or to the Crossbills of North America and ‘ecological speciation’.

As every birder knows, Crossbills’ bills are highly specialised for extracting seeds from conifer cones. In North America Crossbills with differing call types specialise on different conifers and have bill differences adapted for the particular cones. The Crossbills' calls create flock cohesion whereby birds with the same calls forage together and choose mates from within the flock. Ornithologists studying the Crossbills believe that changes taking place plus interplay with squirrels mean that ecological speciation is taking place and that there are now six species of North American Crossbills, the latest one Cassia Crossbill.

Like all science, the science of evolution is never settled but taking place as we speak. “Science is the pursuit and application of knowledge and understanding of the natural and social world following a systematic methodology based on Evidence.”

Such a book would not be complete without the author reminding readers of the perils facing birds in Chapter 12 Evolution and Extinction. Since 1970 bird populations in North America have declined by 29%, a loss of 3 billion birds. At least 40% of the world’s species of birds are in decline with 1 in every 8 species threatened by complete extinction. Birds alone are not in peril. In the 541 million years since animals first diversified, there have been five mass extinctions. Many biologists are convinced we are near a sixth mass extinction uniquely caused by the actions of a single species, man.

If there’s a reproach to be made of the modern day birding it is that birders focus overmuch on the rarity aspect without displaying that element of curiosity, the “what, why and when” of birds. It is a fact of the current birding scene that many do not trouble themselves too much about birds’ life histories, their day to day existence, or how birds came to be.

How Birds Evolve is a moderately technical book to test the desire to learn more, to fill that gap, a book that with just a little perseverance will encourage even the most unimaginative twitcher to cast their bins beyond immediate vistas and inspire them to evolve into a more rounded birder.

How Birds Evolve is accessible, exhilarating science for everyone – amateur birder, professional naturalist or just the average man.

It’s a great book and one to read over and over and I thoroughly recommend it to all.

This is already my Bird Book of 2022 and I can't see it being bettered.

Price: $29.95/£25.00

ISBN:9780691182629

Published (US):Oct 19, 2021

Published (UK):Jan 4, 2022

Pages:320

Size:6.12 x 9.25 in.

Illustrations: 48 colour + 67 b/w illus. 4 tables.

Stay tuned to Another Bird Blog for news, reviews, birding, bird ringing, bird photos and much more.

And remember folks ....................

_(26223659913).jpg)